Research Highlight: A comparative study of the hazards that packages experience in the FedEx and UPS shipping systems

Image 1. Parcel movement during the comparative study of hazards experienced.

The coronavirus pandemic has intensely transformed the imminent progress of e-commerce. It reshaped consumer behavior as social distancing, quarantining, store closures, and lockdown regimes pushed consumers to shop online and vendors to sell online. Thus, e-commerce has grown rapidly as consumers demanded convenience, security, and multiple delivery options. Goods are handled and shipped as part of a complex network of distribution supply chains. These are networks of facilities and distribution options that procure materials and transport finished products to customers. One key process of a supply chain is the physical distribution that involves moving the products throughout the supply chain.

Transportation is a vital component as the transportation of a product, whether inbound to the warehouse/distribution center or outbound to the customer, requires adequate handling. Improper treatment may result in customer dissatisfaction, damaged goods, higher costs, poor service, or even unnecessary levels of inventory. To meet demand, supply chain distribution systems have emerged to ensure that deliveries are made at the most efficient rate possible. Package delivery companies like FedEx and UPS utilize various conventional modes of transportation to deliver various types of packages.

During the holiday season, the increased number of package shipments put extra stress on parcel delivery companies. This extra stress could lead to increased handling severity. The pandemic caused a boom in the e-commerce sector and increased the number of packages that are shipped through traditional parcel distribution channels. In addition, due to restrictions and safety precautions due to COVID-19, many delivery companies operated with reduced staff.

Packaging systems and design students at Virginia Tech were interested in whether the increased demand for parcel delivery and the potentially reduced staff at delivery companies resulted in an increase in handling severity compared to the levels accounted for in industry testing standards. This research project was conducted by students Ben McMurray, a senior from Lorton, Virginia, and Hathaipat Janvamethakul, a senior from Samut Prakarn, Thailand. The students also got a lot of help from VT Alumnus, Jonghun Park, who is an Assistant Professor at Ryerson.

The main objective of the project was to measure and analyze the parcel shipping environment within FedEx and UPS from November to December 2020. The goal of the project was to obtain information on the harshness of holiday delivery during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Two sizes of packages were examined: a small box with dimensions of 7.25 in. x 7.44 in. x 5.13 in. and a weight of 1.9 lbs., and a medium box with dimensions of 14.25 in. x 12 in. x 6 in. and a weight of 3.34 lbs.

All packages contained a Lansmont 3x90 or 9x30 data logger that was protected using a foam enclosure (Image 2). These sensors recorded all vibrations, shocks, and drops that the packages experienced during the shipments. Two shipping routes were investigated. Shipping route 1 was between Blacksburg, Virginia, and Costa Mesa, California, representing a long delivery route in the U.S. Shipping route 2 was between Blacksburg, Virginia, and Toronto, Canada (Image 1), representing an international delivery; a lot of goods purchased through e-commerce channels in Canada come from the U.S.

Image 2. Instrumented box used during the study.

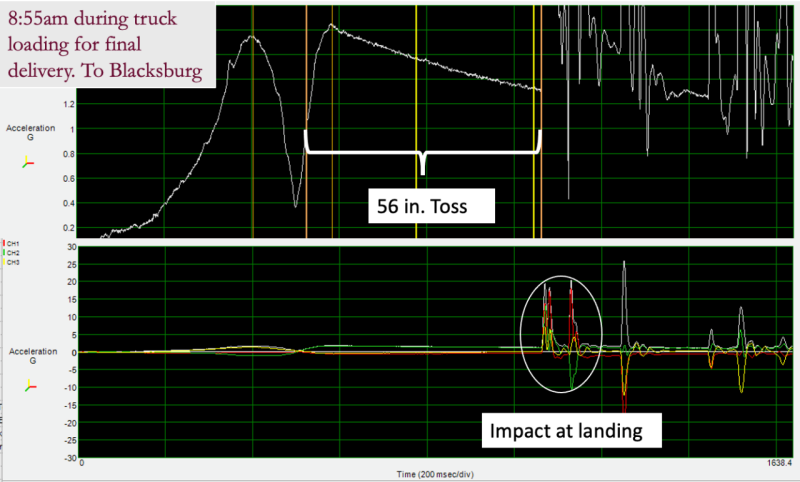

The students found that the packages experienced an average of 124 impacts, out of which an average of 26 impacts were considered significant. The ISTA 3A standard only allows 17 impacts, which is well below the observed values. The results revealed that packages can experience much greater impacts during the parcel delivery that is happening during the COVID-19 pandemic than what is tested for during preshipment procedures. Some of the impacts were equivalent to free fall drops of 89 in.; per standards, packages are only tested with 24 in. drops. In one case, the sensors picked up an event where the package was tossed 56 in. during the loading process of the vehicle during a return trip to Blacksburg (Image 3).

Although there were multiple impacts that were above the industry norm, the students found that 90% of the impacts were below 25 in., which confirms that the industry accepted pre-shipment tests cover the majority of impacts experienced by packages.

Image 3. An impact representing a 56 in. toss event and consecutive impacts upon landing were found during the loading of the parcel delivery vehicle during a return trip.

Also, ISTA FedEx 6A testing standard requires 60% of the drops be face drops; the ISTA 3A standard lists 50% of the drops as edge drops, 31% as corner drops, and only 19% as face drops. This study found that the majority of drops for small boxes were corner drops (44.16%) while the medium boxes experienced mainly edge drops (58.97%). Thus, the ISTA 3A test protocols accurately represent drop orientations that the packages experience during parcel delivery while the FedEx 6A test protocols do not. ISTA FedEx 6A mainly focuses on face drops, which were found to be the least common in this study.

Therefore, this study concluded the following:

- 90% of the drops experienced by packages are below the drop height limit recommended by ISTA 3A.

- Packages experienced a greater number of drops during physical delivery than what they are subject to via the testing standards.

- The drop orientations used in ISTA 3A better represent drop orientations observed during the study than the drop orientations used in the ISTA 6 FedEx standard.